“Private debt” is an asset class fund managers can invest in alongside other assets such as bonds, loans and equities. It has been receiving a lot of attention recently as funds under management swell globally. The growth of the asset class is a positive for companies seeking funding away from banks and public debt markets, and testament to the potential returns available for investors. But the fast growth also poses a risk.

As more and more funds chase lending opportunities, competition for transactions risks compromising returns and lending standards in what is a riskier part of the credit spectrum.

Opportunities for good risk-adjusted returns exist, but investors need to remain disciplined in their approach to private debt, and not get caught in hype; caveat emptor.

There is no exact definition of private debt. In its most simplistic form, the term refers to lending to companies that takes place outside public debt markets or the traditional banking system.

One of the most common forms of private debt is direct lending by a fund manager to a company. For the company, it offers an alternative to banks and public debt markets. For the fund manager, it can offer higher potential returns than public debt to compensate for the higher potential risks: i) borrowers are typically riskier (more akin to low credit-rated companies), and ii) have lower liquidity. Liquidity refers to the fact that usually the loans cannot be readily bought or sold, and therefore the funds that invest in private debt have longer investment horizons, more like that of private equity.

Broader definitions of private debt include Asset Backed Securities (ABS), a particularly large component of the Australasian private debt market. ABS are securitisations – entities specifically established to hold a pool of assets such as mortgages, vehicle loans, and credit cards. The entity then borrows against these assets and their associated cash flows (e.g. mortgage receipts) to engineer higher equity returns.

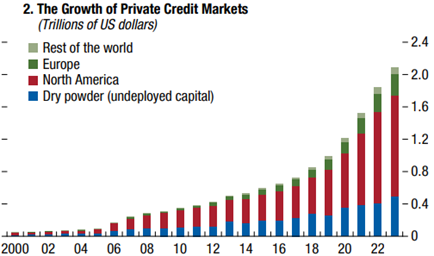

Private debt has grown in relevance since the global financial crisis, when companies sought alternative funding sources during the market volatility. In addition, increasing regulation on banks encouraged banks to step back from lending to corporates, especially higher risk corporates. Recent growth has been further fuelled by the market volatility caused by Covid, and investors’ ‘hunt for yield’ in the low interest rate environment that followed.

While the definition of private debt can be broad and data difficult to aggregate, the chart below from the IMF1 demonstrates the accelerating growth of private credit (primarily direct lending) over recent years.

The increasing cash being allocated to private debt, however, poses some system risks. As more and more funds chase lending opportunities, competition for transactions can cause a “race to the bottom” for returns and lending standards, increasing the risk of inadequate compensation and future credit losses for investors.

From time-to-time, events such as fund manager Blackstone’s default on loans, backed by certain commercial property assets last year, reminds investors of the opacity of private debt markets and the difficulty in gauging broader market health. Borrowers are not typically rated by rating agencies and the debt does not trade, meaning there is limited third party validation of borrower quality and valuation. While typical signals such as falling prices and default data are absent, deteriorating credit quality has been highlighted by press reports citing concerns from Moody’s, prominent asset managers2, and notable bankers such as JP Morgan’s Jamie Dimon. Regulators and the IMF are also alert to the vulnerabilities of private debt (which sits outside the regulated banking system), and the potential implications its growth and opacity create for broader market stability1.

We think sound investment opportunities exist within private credit, and most managers will remain disciplined on lending standards. However, investors in private debt funds need to remain mindful of the exposure they are taking to the weaker end of the credit spectrum, in a market that at its current size has yet to be tested through a downturn, and via investment vehicles that are typically not able to be exited quickly.

[1] “The Rise and Risks of Private Credit,” April 16, 2024

[2] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/videos/2024-05-22/achilles-khajuria-sees-cracks-forming-in-private-credit-video