Global bond yields have moved higher this year in anticipation of tightening central bank monetary policy. What has been somewhat perplexing however is that bond yields are not higher still given economic growth, falling unemployment and headline grabbing rates of price inflation across financial assets, houses, goods and services etc.

Financial repression taxing savers!

In fact, for many countries bond yields are negative after adjusting for current consumer price inflation (CPI) or when adjusted for market expectations of inflation.

This inflation adjusted yield is known as the real yield. Put simply it is the quoted bond “nominal” yield (market interest rate) minus the inflation rate. A negative real yield means on an inflation adjusted basis the cost of that bond to the issuer is negative! Put another way the value of the bond is being eroded on a real inflation linked basis or the investor is willing to lose money after inflation. That is good news for a borrower but not so good for lenders/ investors. It is what is known as financial repression – a tax on savers to the benefit of borrowers.

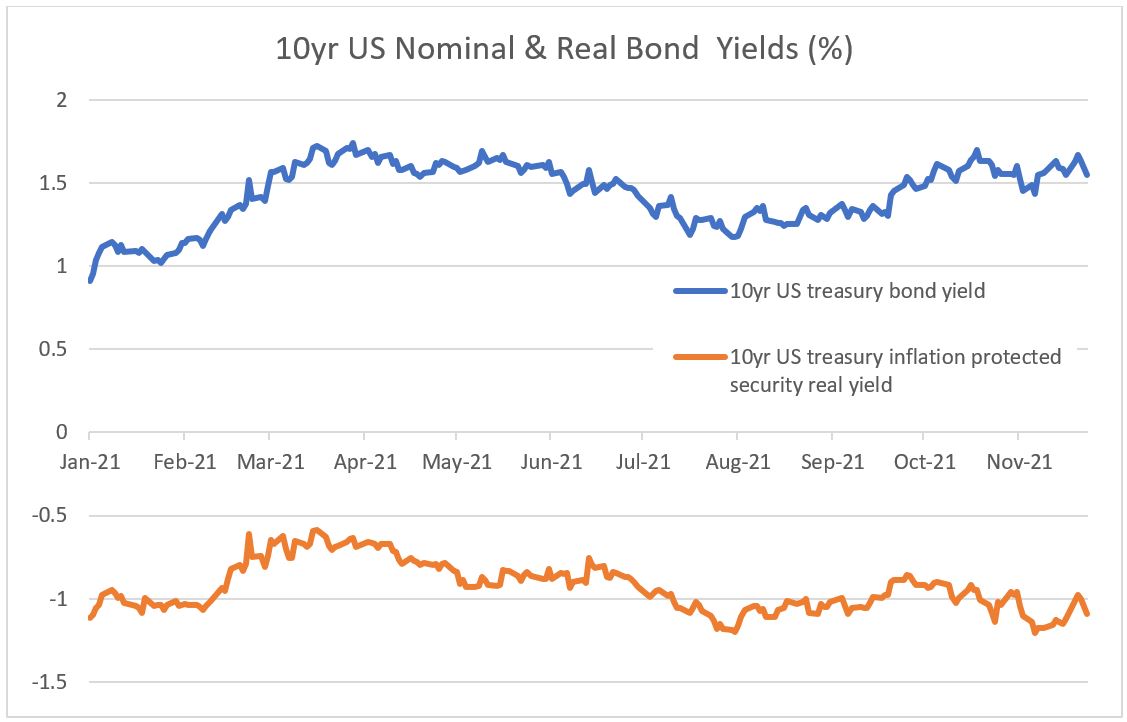

Figure 1: Chart of 10yr US treasury bond yield and the US treasury inflation protected security real yield. The US treasury bond is the US government bond. Its yield is nominal (before inflation). The treasury inflation-linked security is an inflation linked US government bond which essentially represents the real yield on US government debt of that maturity.

Source: Bloomberg

So why is the market not repricing bond yields higher?

Bond supply & demand: The pace of supply of new bonds is reducing but the system remains awash with cash to invest. Many large investors are compelled to buy bonds at any price, keeping prices high and yields low. This includes central banks (quantitative easing buying and buying with foreign currency reserves) but it also includes global pension funds. Deutsche Bank estimate that as much as 60% of the six largest government bond markets are held by this cohort.

A lower neutral cash rate: Central banks estimation of the neutral level of their benchmark cash rates has fallen. This is the rate that is neither expansionary nor contractionary. One of the major reasons for this is the explosion of debt which makes the economy more sensitive to higher rates. For example, in New Zealand the Reserve Bank of New Zealand estimates this rate has fallen from ~4% ten years ago to ~2%. It therefore implies a shallower path for cash rates and so lower longer dated bond yields.

Transitory inflation: Market belief in transitory inflation has waned. Arguably central banks are also noting risks of more persistent inflation. Even after logistics normalize, and employees return to the workforce, risks are that wage and consumer price setting inflation becomes entrenched. But notably thus far longer dated market pricing of inflation does expect a mean reversion back closer to central bank targets, as does consumer and business expectations, as measured by surveys.

Central banks acting: Markets now price an expectation that central banks will raise cash rates to rein in inflation. This lowers the inflation risk for longer dated bond yields, leading to a flatter yield curve, i.e. shorter dated bond yields rise with increasing cash rates but longer dated bond yields fall.

Virus: While the global reopening remains on track, there have been bumps along the way. A new Covid wave in Europe and the risk of more virulent virus mutations mean that some investors still want the safe-haven of bonds in a diversified portfolio, even at anemic yields.

So where to from here?

Long term history shows that real yields have typically been negative when debt levels are elevated, like they are now. For example, US bond real yields spent extended periods in negative territory due to increased debt post the US Civil War and post both world wars. Financial repression is not a new phenomenon!

Markets currently price an expectation that central banks will hike cash rates to reign in inflation. The peak in this hiking cycles will however likely be lower than in previous cycles due to the quantum of debt outstanding. This should lead to a lower yield high on longer dated bonds which may mean future increases in bond yields from current levels will be smaller than feared. For savers bond and deposit returns could remain disappointing versus history, even if lower inflation reduces the extent to which their real yields are negative.

In and of itself that should ultimately provide a favorable backdrop for higher yielding bonds, such as corporate bonds, but also shares.

All that said, and as we have stated before, this truly unique economic cycle ensures considerable risk around any forecast and so remaining flexible and active in managing developing risks will be key.