Coming out of the Covid-19 lockdowns, there was a lot of debate over how the recovery would look in Australia. Economists would throw out letters to describe the shape of the economic growth trajectory and by 2022, it seemed most of the alphabet had been used. Looking at Australia’s economy today, it is reasonable to conclude we are in a K-shaped recession – an economy where some households are suffering while others are seeing their wealth and incomes improve.

Fiscal spending has remained elevated while interest rates have been the main tool used by policy makers to slow the economy and cool inflation. Naturally interest rate increases hit those with the most debt the hardest – as is always the case in a rate-hiking cycle.

However, this cycle is particularly nasty on the indebted compared to previous cycles given 1) very high house prices and mortgage levels relative to incomes and 2) the concentration of debt into certain cohorts.

Figure 1 below shows that those aged 31 to 40 years have the highest average home loans. Many bought their first home over the past few years or pushed the finances to upgrade to a larger home to support their growing family. The total debt concentrated in the 31 to 50 age bracket is even more extreme, given many older-age brackets have paid off most or all of their mortgages.

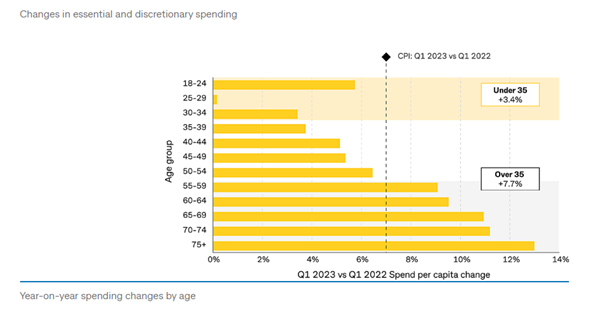

The impact of this is very apparent from CBA’s card spending data released in May. The age brackets over 55 are growing their spending at levels above the 7% inflation rate, while those under 55 are spending well below the inflation rate, particularly those aged 25 to 39.

Source: CBA

Source: CBA

It is also possible that the wealth effect of share markets is nearing – or at – all-time highs again. In addition, much improved interest rates on term deposits are also supporting spending from older cohorts who have the bulk of the savings pools.

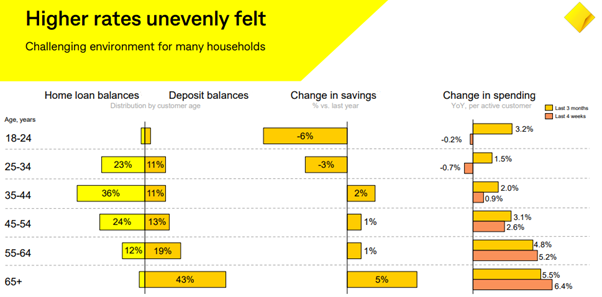

The following new table was released by CBA at its results announcement this week. It confirms that spending of age cohorts over the last few months has continued to diverge.

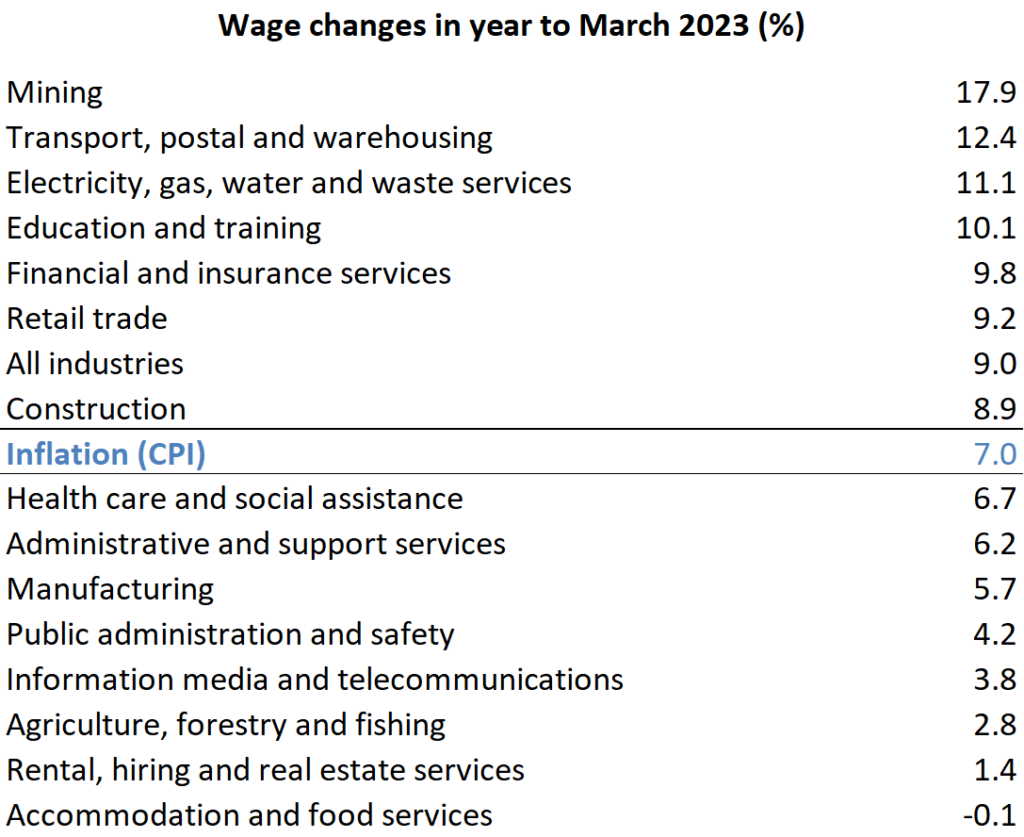

Of course, it is not just mortgage holders or younger people having to tighten their belts. Workers whose wages are not keeping up with inflation will be suffering as their incomes fall increasingly behind the cost of living. The table below highlights some of the industries where wage growth has fallen substantially behind the rate of inflation over the past 12 months.

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Weekly Payroll Jobs and Wages in Australia Week ending 10 June 2023

Many people across all age cohorts working in jobs where wage growth has lagged will be struggling. Those working in mining, however, will be seeing a much-improved real income, even during this inflationary period.

This ultimately highlights the difficult job central bankers still have ahead of them. Their efforts to slow economic growth have not generated a substantial increase in unemployment or even a technical recession in Australia thus far. Even in New Zealand where there is a technical recession underway (two quarters of negative GDP growth) it is difficult to say there is substantial widespread economic weakness.

Inflation remains too high in Australia, although recent data points towards moderation. The problem is inflation may fail to moderate all the way to target levels, given overall economic growth remains robust. Meanwhile, the RBA’s rate hikes are beginning to cause serious pain on large portions of the population. Pushing ahead with further hikes in an attempt to generate a broader slow-down will push those already suffering into increasing distress.

We expect government policy – as is the case globally – to continue to work against the RBA’s inflation goals and provide reactive stimulus to alleviate pain in areas of the economy which are suffering.

Australia is in a K-shaped recession

Coming out of the Covid-19 lockdowns, there was a lot of debate over how the recovery would look in Australia. Economists would throw out letters to describe the shape of the economic growth trajectory and by 2022, it seemed most of the alphabet had been used. Looking at Australia’s economy today, it is reasonable to conclude we are in a K-shaped recession – an economy where some households are suffering while others are seeing their wealth and incomes improve.

Fiscal spending has remained elevated while interest rates have been the main tool used by policy makers to slow the economy and cool inflation. Naturally interest rate increases hit those with the most debt the hardest – as is always the case in a rate-hiking cycle.

However, this cycle is particularly nasty on the indebted compared to previous cycles given 1) very high house prices and mortgage levels relative to incomes and 2) the concentration of debt into certain cohorts.

Figure 1 below shows that those aged 31 to 40 years have the highest average home loans. Many bought their first home over the past few years or pushed the finances to upgrade to a larger home to support their growing family. The total debt concentrated in the 31 to 50 age bracket is even more extreme, given many older-age brackets have paid off most or all of their mortgages.

The impact of this is very apparent from CBA’s card spending data released in May. The age brackets over 55 are growing their spending at levels above the 7% inflation rate, while those under 55 are spending well below the inflation rate, particularly those aged 25 to 39.

It is also possible that the wealth effect of share markets is nearing – or at – all-time highs again. In addition, much improved interest rates on term deposits are also supporting spending from older cohorts who have the bulk of the savings pools.

The following new table was released by CBA at its results announcement this week. It confirms that spending of age cohorts over the last few months has continued to diverge.

Of course, it is not just mortgage holders or younger people having to tighten their belts. Workers whose wages are not keeping up with inflation will be suffering as their incomes fall increasingly behind the cost of living. The table below highlights some of the industries where wage growth has fallen substantially behind the rate of inflation over the past 12 months.

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Weekly Payroll Jobs and Wages in Australia Week ending 10 June 2023

Many people across all age cohorts working in jobs where wage growth has lagged will be struggling. Those working in mining, however, will be seeing a much-improved real income, even during this inflationary period.

This ultimately highlights the difficult job central bankers still have ahead of them. Their efforts to slow economic growth have not generated a substantial increase in unemployment or even a technical recession in Australia thus far. Even in New Zealand where there is a technical recession underway (two quarters of negative GDP growth) it is difficult to say there is substantial widespread economic weakness.

Inflation remains too high in Australia, although recent data points towards moderation. The problem is inflation may fail to moderate all the way to target levels, given overall economic growth remains robust. Meanwhile, the RBA’s rate hikes are beginning to cause serious pain on large portions of the population. Pushing ahead with further hikes in an attempt to generate a broader slow-down will push those already suffering into increasing distress.

We expect government policy – as is the case globally – to continue to work against the RBA’s inflation goals and provide reactive stimulus to alleviate pain in areas of the economy which are suffering.

Month in a Minute: August 2025

Read MoreStock Story: Arthur J Gallagher

Read MoreMilford on Newstalk ZB: 3 September 2025

Read MoreDisclaimer: Milford is an active manager with views and portfolio positions subject to change. This blog is intended to provide general information only. It does not take into account your investment needs or personal circumstances. It is not intended to be viewed as investment or financial advice. Should you require financial advice you should always speak to a Financial Adviser. Past performance is not a guarantee of future performance.