As we enter the second half of the calendar year, central bank policies are entering the next phase of the economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. To get a sense of what actions central banks might take next, we take a brief look back at the actions they have taken since March 2020 and then consider the current economic landscape shaping their decisions going forward.

Governments & central banks reacted boldly

In response to the dire economic sudden stop caused by the COVID-19 outbreak, governments and central banks responded with extraordinary levels of fiscal and monetary stimulus to cushion the economic fallout. For central banks, this included interest rate cuts and quantitative easing (QE), the latter involves central banks purchasing government bonds with newly created money to lower longer term interest rates and provide additional liquidity into the financial system.

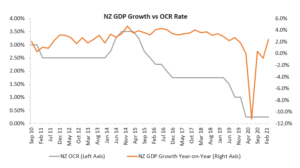

In New Zealand, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) took a range of bold actions. Among others, they slashed the Official Cash Rate (OCR) from 1.00% to 0.25% and for the first time commenced a QE program which allowed them to buy tens of billions of dollars of New Zealand central and government bonds.

Where are we now?

Fast forward to June 2021 and the OCR remains at 0.25%, and from a standing start the RBNZ now holds over 40% of outstanding NZ government bonds.

The dilemma now for the RBNZ is that their monetary policy settings are still in emergency mode, but the economy has recovered faster than they anticipated. GDP growth reported at the end of the first quarter came in at +2.4% year and the unemployment rate was down to 4.7%. Both were significantly better than the RBNZ and markets had been forecasting.

Source: Bloomberg

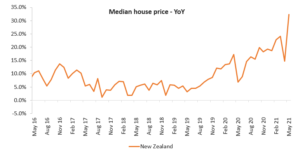

Adding to the RBNZ’s dilemma, the median house price in New Zealand is up 32.3% in the year to May 2021, according to the REINZ, and there are signs of broadening inflationary pressures.

Source: REINZ data

The RBNZ is not alone

Across the world, many major economies are going through a period of explosive growth as economies reopen from COVID-19 lockdowns, amplified by extraordinary levels of fiscal and monetary stimulus.

Central banks must now prepare to manage through this transitory stage. But just as the events that proceeded the outbreak of COVID-19 were unprecedented, the recovery too is unique. The economic outlook remains uncertain and uneven. The dilemma for central banks such as the RBNZ is to manage the unwind of stimulus in a gradual manner so as not to prematurely curtail the economic recovery.

So, what might the unwind look like?

In the case of the RBNZ, they are already tapering bond purchases under their QE programme, which is formally scheduled to run until August 2022. Going forward, they will go from purchasing more than what was being issued by the NZ government to less.

The next step is likely to be interest rate hikes. In light of the May RBNZ Monetary Policy Statement and steady stream of strong economic data, bonds markets are now pricing in a full 0.25% interest rate hike for the February 2022 meeting. When the RBNZ decides to hike will depend to a large extent on when it is likely to meet its objectives for employment and inflation. But the timing of hikes may also depend on whether they use their newly approved macroprudential tools, including debt-to-income limits on mortgages to cool house price growth, and to what extent they are effective.

Uncertainty lies ahead

Although markets are already anticipating a shift in regime from central banks, the outlook for economic growth and inflation is uneven and uncertain. There are likely to be bouts of volatility as markets adapt to the potential reduction of central bank stimulus. Nonetheless, the increase in interest rates and reduction in global and local monetary stimulus is likely to be a slow process, and at the final destination rates are likely to remain historically low.

Conclusion

Milford thinks this transitional process is likely to offer attractive investment opportunities for active management, but it will also need active management to cushion investment returns from the potentially negative impacts of rising interest rates. A flexible investment approach will therefore be useful to match the flexibility that central banks will demonstrate in unwinding their unprecedented pandemic programmes.