News of power outages in China and fertiliser plant closures in the UK are just some of the effects that we have recently seen from a tightening in global energy markets. It has resulted in dramatically higher gas and coal prices with oil recently moving up towards its highest levels since 2014.

This energy squeeze joins a growing list of supply constraints that are causing price spikes and shortages around the world. Initially we saw shortages in semi-conductor chips, new and used cars and certain other goods. Labour shortages have since become more common and now there are energy shortages. All these issues seem to share common causes from either reduced supply, stronger demand in the robust Covid recovery or a mix of both.

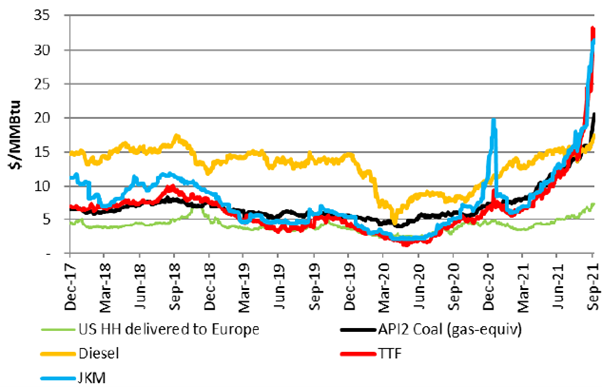

For energy, the tightness is mostly from the stronger than expected demand for power. A good example has been gas and electricity prices in Europe. The recovery in the economy along with exceptional weather conditions and panic buying sparked by low inventories meant demand for both has been stronger than anticipated. With insufficient supplies of Russian pipeline gas, spot prices rallied to the equivalent of over US$200 per barrel of oil recently. This was amplified by Asian Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) prices also spiking as strong demand in China was made worse by high coal prices.

As a result, consumers and businesses are now experiencing rising prices for heating, electricity, petrol and other necessities. This could get worse if the northern hemisphere winter is colder than expected. The good news is that spring will come and heating demand will wane so these elevated prices should eventually be corrected, but things could be worrying in the interim.

But this gets to the key point that if global economic growth out of Covid remains solid, as we all hope, then we need new supplies of energy to come on. Otherwise, elevated energy prices will become more persistent, hurting consumer’s budgets and pushing inflation higher, possibly affecting growth rates. Whilst the shortage of semi-conductors is due to Covid-induced temporary plant closures, the lack of investment in new energy will be no quick fix. Some extra Russian gas will likely be found and OPEC could bring some more oil back, but a more lasting solution is needed.

It has become increasingly hard for companies to obtain funding and approval to build new coal mines and oil fields due to the need to decarbonise. With less investment in fossil fuels, we have hit the capacity level for these markets sooner than we may have thought not that long ago. The current squeeze may not result in more fossil fuel investment and so we could see these markets remain tight over the next decade with higher prices than the past decade.

This leads to the discussion on renewables. With the need for more energy unlikely to be met by substantial new coal and oil investment, this squeeze should spur a quicker move to renewables. Government support is crucial to ensure the right policy settings, but it is a question that every country needs to answer. Maybe things will become clearer at the upcoming COP26 conference?

Our research into this energy squeeze has shown that gas can help this transition to renewables. Whilst still a fossil fuel, it is less carbon intensive than coal and importantly, helps with needed flexibility with renewables such as solar and wind. LNG can play a key role allowing gas to be moved around the world when needed. Over time, the role of batteries and hydrogen (plus some new cool technologies) will be able to fill this role, but they are not yet fully developed viable energy options.

The decarbonisation of the global energy requirements has mostly focused on the need to reduce global warming via new renewable energy sources. The current energy squeeze will heighten the urgency that is required and less carbon intensive sources of energy such as LNG will have an important role to play in the transition to a renewables-based energy future.