The New Zealand share market did not bat an eyelid at last weekend’s election outcome. This is not just because investors are distracted by a global pandemic and record-low interest rates. It is also because the market is anticipating a second-term from a centrist government focused on maintaining the status quo.

Following the formation of a Labour-led coalition in 2017, business confidence plummeted and an already stalling housing market quickly shuddered to a halt.

Three years later, the most common criticism of the government is a lack of accomplishments. But while election promises remained unfulfilled, so do threats such as a capital gains tax. Corporate New Zealand squealed at the adoption of early policies such as minimum wage rises, the repeal of 90-day trial periods and greater collective wage bargaining. Yes, GDP growth has slowed and some businesses have seen profit margins tighten, but for the most part these changes have been absorbed with limited indigestion.

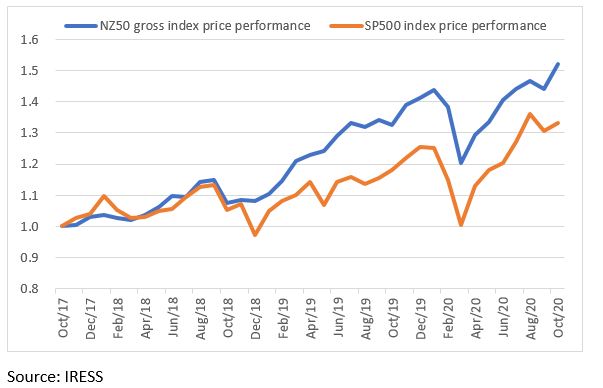

The performance of the NZ50 gross index is worth noting in this context. It rose 53 percent in the three-year term of the prior Labour-led coalition against a 36 percent rise for the S&P500 index over the same time-period. Share market performance is not driven by government policy; it reflects a melting pot of influences including interest rates, economic performance, individual company performance and market dynamics. But it is a neat illustration that a left-of-centre New Zealand government hasn’t disrupted market performance, particularly given the US has been governed by a business-friendly President who has tried to take the credit for the performance of his country’s share market.

The Labour government didn’t drive share market performance, but didn’t upset it either

So what does the market expect from a second-term Labour government with little policy detail to guide it?

Business has already begrudgingly accepted that the minimum wage will continue to rise and sick leave entitlements will increase. Yes, the cost of doing business is going up, but the cost of debt has gone down.

However, there is one large caveat in the muted response from business and markets: that lack of policy now means lack of policy later. Corporate New Zealand is optimistic that the Labour Party will be too busy protecting the economy from a COVID-driven downturn and trying to keep its new National voters on-side to surprise them with anything too business-unfriendly. Business confidence and investment will take a turn for the worse if this does not prove to be the case.

Unfortunately, we are without the buoyant economy that could make ‘no policy and no action’ a desirable outcome. With interest rates at near zero, monetary policy has limited room to provide further economic stimulus. Fiscal policy needs to do the heavy lifting in guiding the economy through the COVID crisis, which will continue well into next year and potentially beyond. This policy needs to be targeted, coordinated and effective in order to keep government debt from increasing above the already high estimates.

For now, these considerations are not front of mind for markets. It is COVID-19 and the border strategy that will impact the economy and drive share market volatility more than government policy. It is appropriate then that this is also preoccupying the government.

But policy must come later, and its impact in a post-COVID economy will be greater than over the prior term. Business will be watching when it does.