Recent economic data has been strong and points to a quicker recovery from the pandemic than the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (“RBNZ”) was forecasting. With many economists expecting the RBNZ to raise the Official Cash Rate (“OCR”) this month, the conversation has moved from if the OCR will rise to how fast it will rise.

The data

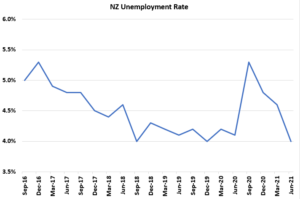

Last week’s very strong employment numbers confirmed the tight labour market many businesses have been calling out for some time. June’s headline unemployment rate at 4.0% is back at pre-pandemic levels that many associate with the RBNZ’s mandate for maximum sustainable employment.

A key question for the RBNZ is how much of the improvement is due to temporary factors? Border restrictions limiting the supply of labour and fostering greater demand for domestic goods and services may subside when borders eventually reopen.

Source: Bloomberg, Statistics NZ

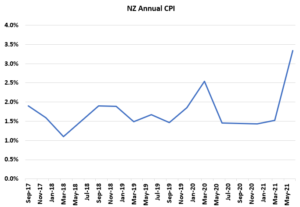

The same consideration is true for inflation. June’s strong headline annual CPI rate of 3.3% will also include temporary elements such as those arising from strained supply chains and pent-up post-pandemic demand.

Source: Bloomberg, Statistics NZ

The reaction

While the RBNZ will be wary not to tighten monetary policy on data that may prove transitory, economists at the big four local banks have seen sufficient strength in the economy to unanimously forecast three 0.25% OCR hikes this year (to 1.00%) commencing at the next OCR decision on 18 August – and further hikes next year. Market expectations were quick to reflect a high chance of a 1.00% OCR by the end of the year.

Source: Bloomberg, Statistics NZ

A foregone conclusion?

While the five rate hikes over roughly 18 months that some economists expect is possible given the current strength of the economy, we also see reasons as to why the RBNZ may be more patient in its approach:

- There is more household debt in the system meaning the economy is more sensitive to interest rates, especially from exceptionally low levels.

- The RBNZ is currently consulting on macro-prudential tools such as loan to value and debt-to-income ratios which could be used to tighten bank lending and dampen house price inflation. In turn this could dampen elevated spending associated with the ‘wealth effect’.

- The effects of monetary policy can take time to show and the RBNZ may want to pause for periods to assess the impact of its policy against an uncertain global backdrop.

We see the same reasons and lower rates globally limiting the extent to which the OCR can ultimately rise over the medium term and expect a medium term ‘peak’ OCR at levels lower than previous cycles.

Conclusion

While current economic data reveals the need for monetary policy tightening away from what are still emergency settings, the ultimate pace of OCR hikes will be determined by an environment that will continue to evolve over the coming months.

Higher rates may provide a general headwind for both equity and fixed interest investments, however, we expect active management to cushion against this as well as seek to benefit from opportunities that may arise from the transitioning rates environment.