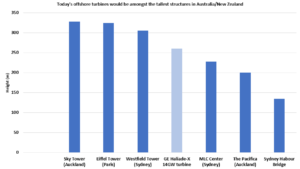

Offshore wind farms are impressive structures. The latest turbines stand 250m tall, with rotors sweeping an area three times the size of Eden Park, each turn generating enough power to run a house for two days. Installed in groups of several hundred spaced a kilometre apart, it’s no wonder that many wind farms become tourist attractions (Scroby Sands in the UK claims to have 35,000 visitors a year!)

Source: Google

Source: Google

This (literally) revolutionary technology was initially developed and commercialised in Europe, but it’s fair to say is now taking the world by storm. Indeed, a wave of new developments are in the works off the coasts of New York, Hawaii, California, the Gulf of Mexico, Vietnam, South Korea, Japan, Taiwan, India, and China. Paris Agreement commitments would, by themselves, see global capacity rise tenfold by 2030.

It turns out that offshore wind power has several advantages over the land-based renewables that we are probably more familiar with, including:

-

- Less chance of Nimbyism (opposition by residents to proposed developments in their area). In many cases the only major landowner involved is the Government.

- Reduced visual pollution. Farms can be sited further out to sea or completely over the horizon.

- Improved proximity. Farms can be conveniently positioned close to many coastal cities and industrial areas.

- Enhanced power production. Winds offshore are generally more consistent than those over land, resulting in more power produced compared to onshore windfarms, and at more useful times of the day than solar.

Limited airtime in Australia so far – but the tide is turning

To date there has been little sign of these behemoths in our corner of the world, despite Australia and New Zealand having some world class wind resources as well as existing offshore oil and gas industries to draw skilled workers from.

However, without a lot of fanfare, earlier this month the Federal Minister for Energy and Emissions Reduction tabled two bills in the Senate that aim to establish a framework for offshore energy infrastructure of many types, including offshore wind. Already there are at least 10 Australian projects waiting for the legislation to be finalised, representing capacity of over 25GW (or more than 10 Huntly Power Stations). Perhaps the furthest along is the 2.2GW ‘Star of the South’ off the Gippsland coast which, when commissioned late-decade, could singlehandedly provide for 20% of Victoria’s power needs.

Why is this also important for New Zealand?

In a word, scale. Such massive structures do not come cheap, with a sticker price of around US$10 million a pop plus the not inconsiderable cost of specialised equipment needed for installation, servicing, and decommissioning.

The International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) estimate that both total installed costs and lifetime ‘levelised’ costs per unit of output have nearly halved since 2013, partly due to economies of scale. Australian and NZ volumes combined will make things that much cheaper – especially as the massive size of the units means local production is essential to cut down on transport costs. This could see turbines erected in New Zealand waters years earlier than would otherwise be the case.

It takes anywhere from 3-5 years to design and permission a windfarm and another 3-5 years to build it. But when you finally do jump aboard the tour boat for your first up close experience with a Kiwi-based offshore wind farm, maybe sometime in the 2030’s, just remember – it all started here.

Milford’s view

Milford continually keeps track of the latest global innovations. We think that the offshore wind farm industry could be a powerful investment opportunity in the future, and hold shares in both the global #1 and #2 in this space, Denmark’s Orsted and Germany’s RWE.