Market expectations for the Official Cash Rate (“OCR”) to go negative next year are increasing. The Reserve Bank of New Zealand (“RBNZ”) has suggested that this is a real possibility if further monetary policy support is required. Negative rates should provide scope for lower borrowing and saving rates, but the extent of this and its impact remain uncertain.

On cutting the OCR to 0.25% in March, the RBNZ declared it would keep the OCR at this level until March 2021. Subsequently, as the crisis deteriorated, further monetary policy support was needed. Rather than breaching this commitment the RBNZ instead pulled other policy levers, most notably quantitative easing via its Large Scale Asset Purchase (“LSAP”) programme (as previously discussed here).

These decisions may have been due to required support for the government bond market given the huge increase in government bond issuance. It also transpired that that the New Zealand banking system was not operationally prepared for negative wholesale interest rates.

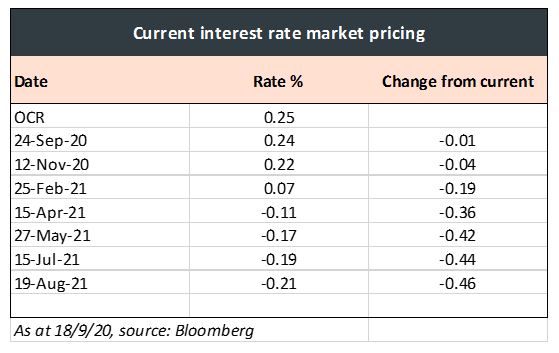

Looking ahead, while further increases to the LSAP programme are possible the RBNZ has indicated that if further monetary policy support is required, it could lower the OCR further, including considering a negative OCR. Indeed, the RBNZ has required NZ banks to be operationally prepared for negative wholesale rates by the end of this year. Interest rate markets are therefore now pricing in a high probability of a negative OCR.

How would a negative OCR impact banks?

The OCR is the conventional monetary policy tool the RBNZ uses to influence interest rates in New Zealand. A lower OCR lowers short term wholesale money market interest rates. The RBNZ does not, however, directly impact retail interest rates as these are ultimately set by the retail banks for their clients. That said, the RBNZ has stated their belief that a negative OCR should not mean negative retail rates. This is supported by the experience offshore where some countries have experienced an extended period of negative central bank rates.

These circumstances are a problem for retail banks. In a gross simplification, retail banks will have to pay an interest rate of zero or above on client cash balances but will receive a negative interest rate when these are deposited at wholesale rates or with the RBNZ. That would reduce bank profitability by reducing their interest margin. This is the nexus of the argument against the efficacy of negative interest rates as if banks are earning less, their profitability suffers and they will be less likely to extend credit to the economy.

To mitigate the negative impact on banks, the RBNZ is proposing that a negative OCR would be accompanied by some form of funding for lending, at a rate likely just higher than the OCR. The form of this or similar programmes are still to be determined.

What does this mean for retail interest rates?

A negative OCR should translate to lower retail interest rates. The move lower may not be uniform, and some retail interest rates may have limited scope to change. We summarise these into four broad categories:

- On call retail bank accounts that attract the OCR or an interest rate close to zero already would likely only fall to an interest rate of zero if the OCR went negative.

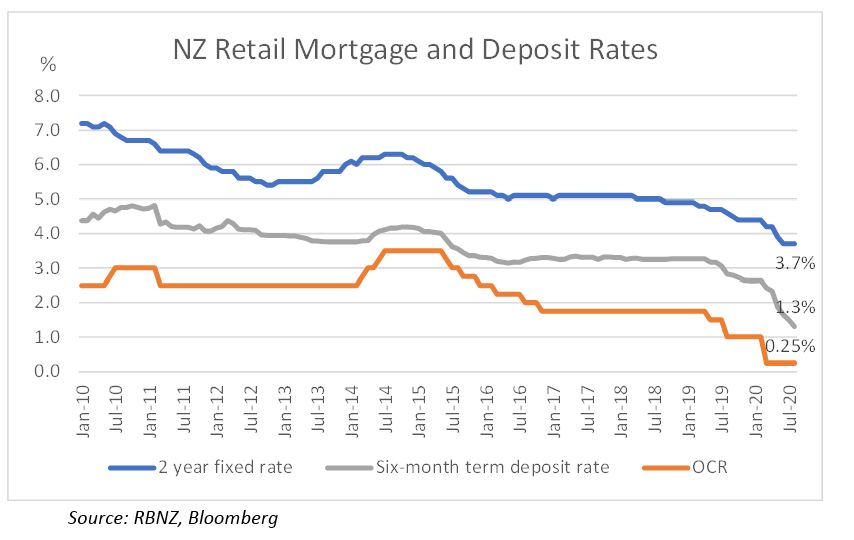

- Retail term deposit rates have been falling concurrently with a falling OCR but in general over recent years carded retail term deposit rates have been significantly above the OCR (see chart below). This is due to banks competing for domestic deposits, cognisant that regulation (even if currently more relaxed) requires a proportion of their lending to be deposit funded. Nonetheless, with a lower OCR these rates will also fall but likely retain a small positive interest rate.

- Retail lending rates (mortgages but also unsecured lending) should fall but as the aggregate interest cost for banks will not fall in line with the OCR (for the reasons outlined above) they are likely to fall less than the fall in the OCR. Moreover, banks still need to earn a margin above their cost of funding for the risk they take for lending to households and corporates – per the chart below, the current difference between the OCR and a two year fixed rate is approximately 3.5 percentage points, and

- Interest rates on corporate and government bonds may fall further as investors hunt for positive returns.

The chart below shows that while the OCR has fallen 0.75 ppts in the year to August, the two-year fixed mortgage rate has fallen 0.80 ppts and deposit rates 1.5 ppts.

Should the OCR go negative, we see scope for retail borrowing and deposit interest rates to fall, but as noted by the RBNZ, “don’t expect your mortgage or your deposit rates to go negative”.