Environmental, social and governance (ESG) considerations have become a core part of the investment decision making process for most asset management firms, just as they are for Milford. No longer an afterthought or box ticking exercise, ESG is prominent in company reports, management presentations and in investor thinking – which, for many companies, was certainly not the case until recently. This article discusses the changing ESG landscape, with reference to environmental risks associated with climate change and decarbonisation and how they may shape the outlook for the global aviation industry.

ESG risks have become a key area of focus for the corporate world today. Shifting societal attitudes and social media play a role, as does shareholder activism, notably from superannuation and sovereign wealth funds, various ethical funds, as well as pressure on the broader funds management industry.

Recent high profile ESG matters brought to the public attention in Australia have included Rio Tinto’s destruction of cave sites containing Aboriginal art and artefacts[1], and promotion within AMP of an individual with a history of sexual misconduct – which in both cases led to the departure of senior management.

Many ESG considerations are core to investment decision making, with real world implications for future operating environments, cashflows and therefore valuations and share prices. Understanding corporate culture can be abstract but management track record and reputation are important, as are internal corporate ESG policies and targets, and ratings from independent ESG ratings houses such as Sustainalytics and ISS.

For some industries, particular ESG issues are endemic and require fundamental research to understand how trends will evolve. An example of this is global aviation and the implications for the sector from climate change and global decarbonisation. An industry crippled by Covid19 restrictions on travel, faces further headwinds as a carbon intensive industry.

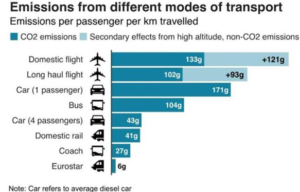

In 2018, transport industries produced 25% of global emissions, of which aviation contributed about 12% (i.e. 3% of total emissions), while cars and trucks produced 74% (source: IEA and ICCT). While the aviation industry’s share in total emissions is small, there are other important considerations: relative carbon intensity, substitution, policy, and technology.

Carbon intensity

On a passenger km basis, aviation is the most carbon intensive passenger transport industry. Short haul flights are particularly bad as they spread the high fuel burn of take-off over a shorter distance.

Figure 1: Source: BEIS/Defra Greenhouse Gas Conversion Factors 2019

Figure 1: Source: BEIS/Defra Greenhouse Gas Conversion Factors 2019

Substitution

High speed rail is 40x more CO2 efficient vs. short haul flights and can be a viable substitute for trips of up to about 1,000km. Cars are also less carbon intensive and are likely to decarbonise through electric vehicles (and become autonomous) at a faster rate than aviation.

Policy

With much of the world targeting climate neutrality by 2050, as well as shorter term reduction targets, the tides of policy are against carbon intensive industries. The European Commission aims to double high-speed rail traffic within ten years and to triple it by 2050. In France short haul flights were recently banned where there is a train trip available of up to 2.5 hours (with similar measures being discussed in Spain). The Swedish concept of flygskam (or flight shame) is illustrative of changing societal views. In New Zealand, a recent report by the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment recommended a distance-based departing passenger tax to be incorporated to airline tickets which can be used to fund climate-related initiatives. Similar taxes are being discussed in France and Spain to disincentivise air travel.

Technology

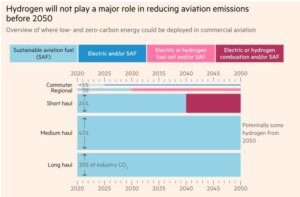

Global air passengers are expected to normalise post-Covid and continue to grow with the notable tailwind of emerging middle-classes in China, India and elsewhere. And the outlook for cleaning up the industry is opaque, with sustainable aviation fuels (which are currently prohibitively expensive), carbon offsets, and flight path optimisation the most viable options for over the next decade, with hydrogen planes further off.

Figure 2: Source: Air Transport Action Group

Figure 2: Source: Air Transport Action Group

There are clearly a raft of important environmental risks that will be important for companies in the aviation industry. How policy evolves and how the industry responds in terms of cleaning up and pushing technology forward, will be crucial. While this discussion does not reach definitive conclusions for the sector, it should be clear that environmental risks need to be considered when investing in this space. That is certainly the case for Milford; these risks frame the conversations we have with industry participants such as airports, airlines, and aircraft, jet-engine, and parts manufacturers. The brief introduction above on the aviation sector illustrates more broadly the importance of ESG as a core part of investment decision making.

[1] As shareholders in Rio Tinto at the time of the blast, Milford advised the company their initial response was inadequate and showed cultural failure rather than a shortcoming in policy. More information can be found here