In between graduating from university and starting work, I volunteered for a charity that built birthing suites in remote villages in Tanzania. Tanzania is a developing nation, and the remote regions operate on a subsistence farming basis. One day a local leader took a group of us to his store of corn. As he opened the rickety door to his shed to show us around 200 drying cobs, he beamed with pride and pointed to his stomach. He intimated that his family would not be going hungry any time soon. That pile of aging, dry corn was his savings, not for a rainy day but for a season without rain.

In many ways the Tanzanian farmer’s corn store is like our family savings. Ours are represented in monetary terms but also reflect years of hard work and even inter-generational transfers. His responsibility for his store is like the responsibility we feel for our savings. They bring us a sense of security. They also enable us to partake in bucket-list experiences in retirement and can provide a legacy for our children and/or our charitable interests.

It is no wonder that we often react to falling asset values in the same way that the Tanzanian villager would react to a fire approaching his store of corn. When asset prices fall our brains react in a “fight or flight” manner and we often seek the safety of cash without stopping to engage the rational, decision-making part of our brain. This is because, as a species we have spent many more generations living like the Tanzanian villager than a modern saver with access to international capital markets.

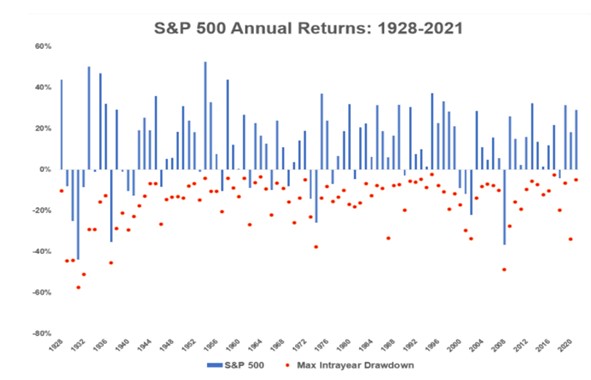

The rational part of our brain would note that stock prices often drop by 10% or more. For example, in 59 of the last 94 years there has been a fall of 10% or more in the S & P 500 index, yet that index has returned 867,100% in total over that time frame (including dividends).

Source: https://awealthofcommonsense.com/2022/01/this-is-normal/

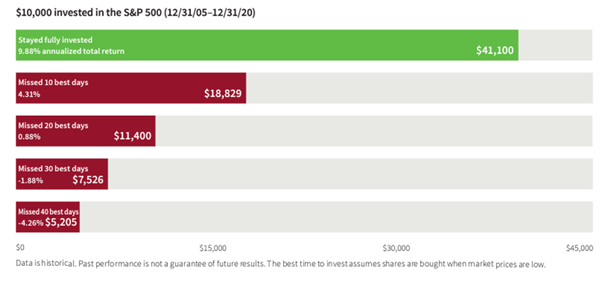

The other problem with selling during these downturns is that it is almost impossible to re-invest at the lows. Markets often start to rebound, not when the news is good, but when it starts to get less bad. So, almost by definition, to re-invest when the markets are at their lowest point, an investor who sold when the “fire had just started” would have to buy back in when the “fire was raging at its worst”. Often the largest daily returns from investments occur at these low points and the graph below shows the effect of not being invested on just a few of these high returning days.

Source: Putnam Investments

The good news is there are a few things that an investor can do to prevent irrational reactions to falling asset prices.

- Seek professional financial advice before setting up an investment plan.

A Financial Adviser can help to structure your investment to align with your long-term goals . This means that when volatile periods in markets arrive, you know that this is normal, and it does not affect your long-term goals. Your adviser can also assess your risk tolerance and capacity. They will help you select an appropriate strategy that will ensure that any surprises in terms of market volatility are kept within your comfort range. Financial Advisers are also experienced in managing portfolios in a variety of different market situations and can provide expert advice when it matters most. - Consider using an investment manager that has a good long-term track record of managing through the inevitable downturns.

At Milford we believe that active management can not only add to returns in good economic times but can also limit the downside when the investing environment is less favourable. - Regularly review your investments.

A good Financial Adviser will ensure you do this regularly and when your personal circumstances change, preventing negative surprises. They will make sure your investment strategy remains consistent with your goals, checking that your risk tolerance or capacity hasn’t changed. If you don’t have a Financial Adviser, there are a number of tools available on our website that can help you understand your risk tolerenace and check you are on track to meet your goals. - Talk it through

If at any point you start to feel nervous, call your Financial Adviser if you have one and talk it through with them. They’re there not only to manage your investment strategy but to be your guide and coach when needed. Often, all it takes is a quick chat to pull us back into that rational mindset needed to make good financial decisions. At Milford, we’ve created a Digital Advice tool that can help you choose the right Milford Fund for your situation.