Much attention from financial markets has been given to inflationary indicators in global economies; inflation being a key consideration for central banks when setting monetary policy.

Locally, the NZIER Quarterly Survey of Business Opinion was released on 13 April. A net +28% of firms said they intend to raise selling prices, well up from +15% the previous quarter. Furthermore, there is an increasing number of businesses who believe their costs base will rise, with a net measure of +48% being the highest level since September 2008.

Inflation is to be expected here in New Zealand, with record levels of fiscal and monetary support, minimum wage hikes, supply chain disruptions and pent-up demand following a year of lockdowns and uncertainty.

What is, perhaps, more interesting is the strong outlook for hiring intentions, with a net +18% of businesses stating that they intended to hire. Such a print should read well for future economic growth. However, the achievability of these hiring intentions is not clear, with already low unemployment rates and population growth curtailed by border controls in the short-term. Indeed, firms reporting difficulty finding labour increased for both skilled and unskilled labour.

Therefore, whilst costs and prices rise, output capacity appears constrained, at least in the short-term; raising the possibility of stagflation. This is particularly troubling for firms who are unable to pass the full impact of rising costs through to customers, which seems to be the case with +21% of firms seeing profitability fall in the quarter.

This is the manifestation of an issue that has been looming in New Zealand for the past decade. Specifically, economic growth has been underpinned by population growth in the past decade, driven by movements in net migration as opposed to gains in productivity.

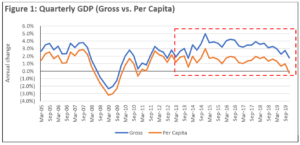

Recently released findings from the Productivity Commission suggest the productivity of leading companies in New Zealand is on average less than half of that found in the top companies in other small, advanced economies (e.g. Singapore and Denmark). This is evidenced by a divergence of annual gross GDP growth and GDP growth per capita, something that has put significant pressure on infrastructure and the housing market.

Source: Stats NZ

Source: Stats NZ

The solution, then, is to focus on achieving future growth via productivity gains. Rising input costs and diminishing capacity should increase the relative attractiveness of capital investment to increase productivity. This is enabled by an all-time low cost of debt and significant ‘dry powder’ in both public and private capital markets. Furthermore, the economic recovery from the COVID-19 shock should underpin demand, driving returns on capital invested.

A silver lining of COVID-19 is that it has accelerated innovation, forcing businesses to re-think how they operate to compete and survive in a changing world.

In the Milford Private Equity Team, we are on the lookout for private investment opportunities with a focus on value-add innovation, where we can be competitive from New Zealand, rather than pure volume growth plays, where relatively high input costs leave us at a disadvantage on the global stage.

These opportunities can range from early-stage businesses, funding R&D to develop new technology / solutions to improve productivity; mature businesses with the potential to improve efficiency and capacity through automation or a shift to digital; and educational facilitators, with a focus on improving the efficacy of learning, increasing the skillset and capability of the workforce.

Continuing this momentum and creating the platform for productive growth will present attractive opportunities for investors over the next decade.